CHOLERA, CORONAVIRUS AND CHEMICAL WEAPONS: SALISBURY'S SECRET HISTORY OF CONTAGION

- Sarah

- Oct 11, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 16, 2022

To many people, Salisbury has only ever been famous for its middle-England attractions - a pleasant medieval town just off the A303 between London and the summer delights of the West Country. Known for having the tallest spire in England, its proximity to Stonehenge, people wearing barbours and voting Conservative for the past 100 years, Salisbury has always personified sleepy middle-England. All of that changed in 2018 when two Russian agents visited the city, spread Novichok on a door handle and unleashed a chain of events which saw the death of a resident, severe illness in others and the city shut down and in turmoil for months.

The peaceful town was thrust into the international limelight, with news crews arriving from around the world, helicopters circling overhead, half of the city boarded up and politicians talking more about the city in a week than they had done in the city's lifetime. Visitors stopped coming and school children were taught to never pick anything up from the ground unless they had dropped it - an edict which is still in place four years later.

For many, it was the first time they had heard of Salisbury, and to them it will forever be associated with Russian chemical weapons, but the city actually has a history of contagions which goes back to long before the Russians arrived with their wretched poison.

Salisbury and Cholera: a press blackout, an unsung hero and the creation of Salisbury Museum

Cholera arrived in England from the East in 1831, a bacterial disease spread through contaminated water which causes acute dehydration and diarrhea. There were several cholera epidemics across the country, and in Salisbury cholera reached its peak in 1849, when 1300 people were treated at the infirmary and 192 people died in the city in the space of just 2 months, more than any other English city of the same size.

The reason for this was the water courses which ran through the city.

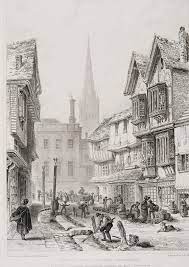

When Salisbury was built in the 13th century, it was constructed on a chequers system with five streets running east to west and six streets running north to south. The River Avon ran southwards and hatches could be opened so that the water would then flow west to east through specially constructed channels along the centre of most city streets and then feed back into the Avon. These provided water and drainage to most of the city. Salisbury acquired the name of the English Venice, but by the 17th century they were just filthy, disease-laden open sewers.

Celia Fiennes (1685) described the streets of Salisbury as, “not so clean or so easy to pass in”, and Daniel Defoe went further, commenting in 1748 that, “the streets were always dirty and full of wet, filth, and weeds, even in summer”. A programme of improvement had been started in 1737 of moving the channels to one side, making brick beds for them, and bridges for pedestrians. Although this may have removed some of the visible unpleasantness, it did not tackle the unseen contamination.

At the time, it was unknown that cholera was transmitted through infected water, and the residents of Salisbury in 1849 could not understand why the disease seemed to be no respecter of class, with the wealthy residents of the Cathedral Close as likely to fall ill as the poorest living in the slums. In fact nine residents of the Close died, including Dr. Richard Brassey Hole, who worked at the Infirmary during the epidemic. He died at the age of 30, and there is a plaque to him in Salisbury Cathedral.

The local paper, The Salisbury Journal, took it upon itself to hide the true nature of the epidemic. They first reported the outbreak in July 1849, saying that '20 grains of opiate of confection and a little peppermint water’ would cure it, as well as staying calm, because fear of the disease could cause it.

Only a week later, they reported that the disease was 'thankfully abating'. However, data collected by Thomas Rammell for the subsequent inquest showed that the number of deaths was continuing to climb, and a local glazier recorded making 60 coffin plates in just a week. The lists of people who had died continued to grow in the Journal, but with no cause of death attributed. By August however, the game was up, and the national newspaper, The Times, reported the correct number of deaths and that the wealthy were fleeing the city. The Journal confessed its omission, saying that they believed the subject was 'too painful' for its readers.

It was another resident of the Cathedral Close, surgeon Dr. Andrew Bogle Middleton, who determined that the disease was being spread through the water courses. ‘Salisbury, which receives . . . all the waters of Wiltshire' has suffered five times its usual mortality, and that ‘the localities which have suffered most severely in this part of the country are situated on the banks of rivers. Wilton, Salisbury, Downton and Fordingbridge are instances of this and these cases confirm the theory of the propagation of the disease by the rivers’.

Middleton believed so strongly that the epidemic was due to the canals, that he undertook to introduce a new system of water-supply and drainage. His proposals were met with fierce opposition, and the Mayor would not allow the Board of Health inspector, Thomas Rammell, to hold his inquiry in the Guildhall, where inquiries had always been held. It was eventually held in the Assembly Rooms, and provided a detailed, grisly account of Salisbury's inadequate sanitation.

The results of Rammell’s enquiry were published in 1851, endorsing everything that Dr. Middleton had said, and gradually the channels were drained, sewers were built and a piped water supply established. The last channel to be filled, in 1875, was the deepest one in New Canal.

This is commemorated by the Blue Plaque which is on the wall of the building which was once the Salisbury Assembly Rooms (but is now Waterstones), in New Canal.

In 1864, Middleton presented his paper, “The Benefits of Sanitary Reform as Shown at Salisbury in Nine Years Experience Thereof” to The British Association for the Advancement of Science” at Bath in 1864 (which you can read here).

Middleton's insistence that cholera was spread through water, and his determination to remove all of the open water courses in the city, predates the official and famous discovery of the transmission of cholera by John Snow in London, who worked out the connection between a water pump handle (which you can see in the Museum of London) and an epidemic in 1854.

On a side note, and for the benefit of historians, when the water channels were filled in, centuries worth of discarded and lost detritus was removed from the water by the workmen. It was Dr. Middleton who wrote a letter to the Salisbury Journal suggesting Salisbury should have a museum. The letter was answered by 95 year old Dr. Fowler, who funded and worked with Dr. Middleton to set up the museum in 1861, with the Drainage Collection being the start of it all. It has over 1300 items, some of which are on display in the current museum. Dr. Fowler also has a blue plaque, on the outside of the old St. Ann Street Museum, but without Andrew Middleton it might never have happened.

There is a plaque and a stained glass window dedicated to Andrew Middleton in Salisbury Cathedral.

Salisbury and the Coronavirus (Common Cold)

In 1942, the Red Cross set up a field hospital in Salisbury suburb Harnham as a blood transfusion centre for allied troops. After the war in 1946, the Common Cold Unit was set up by the Medical Research Council on the site of that former military hospital. Under the direction of Dr. Andrewes, research into the coronavirus was carried out.

Volunteers would stay for up to a fortnight, with it being sold to them as a different type of holiday. They lived in fully equipped flats with three hot meals a day, books and board games and sports facilities on site: many would return year after year. Infected with a cold virus on their arrival unless they were part of the control group, they were closely monitored for all sorts of symptoms including nasal stuffiness, face ache, extra hours in bed and how many tissues they had used. (You can find details on all of the forms they were sent when they registered)

Significant advances in research were made and they proved that over 100 different viruses and rhinoviruses were responsible for the common cold. In 1965 they discovered the coronavirus which they named as such because the virus particles had what looked like a crown on them. They also studied transmission and infection rates and research conducted there was also integral to later work on HIV.

The unit closed in 1989 and a housing estate was built on the site. A plaque (photo coming soon) at the entrance commemorates the 20,000 volunteers who helped with the research, the medical staff and nurses who cared for them.

Salisbury and Chemical Weapons: A secret biological warfare centre

The infamous Porton Down, a highly secretive research base just outside Salisbury, was opened in 1916 to test chemical weapons as a response to the German use of chlorine and mustard gas during World War I. From a few small farm buildings and huts back then, it is now a vast 'science park' near the village of Porton.

Over the years their remit changed to include research on all sorts of chemical and biological weapons, much of which is top secret. Highly controversial and subject to all sorts of rumours and conspiracy theories, many of which were later proved to be true, the base holds some of the world's most dangerous pathogens including Anthrax, Sarin gas, Ebola and of course, Novichok.

It is not a place that can ever be visited, hidden behind secure fencing in the middle of Porton Down, and even people who work there are kept in the dark about all but their own projects. It is just something that the people of Salisbury accept as a sinister but quiet presence on their doorstep.

Salisbury and Chemical Weapons: Novichok

On 4th March 2018, many of us locals were listening to local radio, Spire FM, and heard a news headline of two people found fitting and frothing on a bench in a Salisbury shopping centre. Initially we thought it might be drug addicts, that one of the awful new drugs had found its way to our peaceful city. As the days progressed however, we soon became aware that it was much bigger than that, that former Russian spy, Sergei Skripal, who had been living peacefully in Salisbury, had been targeted by Putin and his henchmen for being a double agent working for MI6 many years before.

Helicopters started circling overhead, news crews appeared, parts of the city were being closed down and boarded up. Word spread of a major incident at the hospital, that others were contaminated by the mystery poison. We all avoided the city centre and wouldn't let our kids go there, with the new edict being drilled into them 'if you didn't drop it, don't pick it up' by schools and parents alike. There were people in white hazmat suits and masks everywhere, conspiracy theories spread rapidly - were the scientists at Porton Down testing their chemical weapons on the local population, was it a 'false flag' operation and just how many Russian ex-spies were living amongst us?

Local pub The Bishops Mill was boarded up as was Zizzi's restaurant, the bench they had been found on was completely removed, the duck and swan population of the city vanished entirely, apparently killed in case they transmitted the contagion (four years on they still haven't returned in the same numbers as before).

Just when things seemed to be settling down, the news broke about the death of a resident who had unwittingly sprayed Novichok on her wrists from a perfume bottle found in Elizabeth Gardens or maybe from a skip in the town centre. More areas were boarded up, with the park off limits for months and months. CCTV footage showed the two Russian spies who had brought such carnage to our city; they were paraded on Russian TV saying they were tourists who had just visited the cathedral, quoting the height of the spire as if to prove it.

Salisbury has become famous across the world for this latest incident in its history of contagion. You can see people posing outside the window of the restaurant where the Skripals dined, taking selfies on the spot where the bench once sat and even asking where they can find the house where it all started (we don't tell them).

You can however visit some of the other sights connected with all of Salisbury's unique history which are on the map below.

Sources:

Comments